THE Fossil Bed Xcursion

THE XCURSION

Driving the Through Central Oregon and The Fossil Beds is very much like stepping back in time! The central portion of this trip follows the Crooked River into Prineville, Oregon and then travels easterly into Post which is considered to be the center of Oregon. Further along the Paulina Hwy brings us along the Izee Ranch Rd and down to Seneca, OR. From there you will travel the Malheur National Forest and the Southern reaches of the Strawberry Mountain Range. Unity, Oregon is a Fueling Destination before you travel into the Burnt Canyon across to Durkee. From here it's North into Baker City where the trip doubles back West towards the more Northern Central Oregon area and the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. The towns, history, and minings, stir the experience towards an adventure of epic proportion on the best roads and scenic byways in our State and the least traveled ones as well!

LOGISTICS

CONSIDERATIONS

Driving the Through Central Oregon and The Fossil Beds is very much like stepping back in time! The central portion of this trip follows the Crooked River into Prineville, Oregon and then travels easterly into Post which is considered to be the center of Oregon. Further along the Paulina Hwy brings us along the Izee Ranch Rd and down to Seneca, OR. From there you will travel the Malheur National Forest and the Southern reaches of the Strawberry Mountain Range. Unity, Oregon is a Fueling Destination before you travel into the Burnt Canyon across to Durkee. From here it's North into Baker City where the trip doubles back West towards the more Northern Central Oregon area and the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. The towns, history, and minings, stir the experience towards an adventure of epic proportion on the best roads and scenic byways in our State and the least traveled ones as well!

LOGISTICS

- Fueling Availability: Should be done prior to leaving Southern Oregon. Medford, OR, Canyonville, OR, Coos Bay, OR, Coquille OR. Grants Pass, OR.

- Fuel and Resting Stops: Medford, White City, Crescent, LaPine. Prineville, Post, Paulina, Seneca, Unity, Baker City, Austin Junction, Dale, Ukiah, Heppner, Spray, Mitchell.

- Total Xcursion Distance: 1289 mi

- Transportation Method: Motorcycle, Automobile Camper, RV. Auto.

- Average mileage: Per day 214 mi.

CONSIDERATIONS

- Don't forget camera gear and swim trunks and a towel!

- Thunder storms are always possible. Be Prepared!

DAY 1 Southern Oregon to Crooked River

Mileage: Crooked River Canyon 221 mi.

Campground: Chimney Rock, Palisades, Cobble Rock, Still Water.

Info: The section of river flows through scenic vertical basalt canyons and is like dropping into another world!

DAY 2 Central Oregon, Malheur, Strawberries, Eldorado Camp.

Mileage: Center of Oregon Strawberries, Elderado C.G.. 208 mi.

Campground: Eldorado

Info: This segment is Scenic, Historical, Curvy, and incorporates wide open view of pristine cattle country. It truly is the center of Oregon.

DAY 3 Burnt Canyon, Deer Camp.

Mileage: Burnt Canyon Deer Camp 139 mi.

Campground: Deerhorn Campground

Info: This small campground offers fishing, exploring, nature watching and hunting opportunities in the Middle Fork John Day River State Scenic Waterway. The campground is busiest during late summer and hunting season. It provides a very fun road adventure on the next day on County Road 20

DAY 4 Umatilla National Forest to Spray

Mileage: The Umatilla to Spray. 165 mi.

Campground: Spray Riverfront Park

Info: A year after Wheeler County, Oregon was officially formed in 1900, John and Mary Spray established a post office on the banks of the John Day River. Over a century later, Spray's settlement is barely even a town, boasting just a few general stores and a gas station. But therein lies Spray's charm: the escape from development. This little town of fewer than 200 residents hosts a quaint and surprisingly full-service community park, however. No doubt the park's main attraction is its access to the John Day River, whether for floating, fishing, or taking a swim on a hot, dry summer day. The park also features restrooms, a large picnic shelter, and six first-come, first-served walk-in tent campsites. The campsites are $12 per night, and a $5 fee is charged for boat launches.

DAY 5 Painted Hills and Fossil Lands

Mileage: The Painted Fossil Stuff! 235 mi.

Campground: Spray Riverfront Park

Info: No packing up to move today! This is a ride day after a little breakfast in town!

DAY 6 Home

Mileage: Home. 321 mi

Campground: Your Place!

Info: The ride from Spray is a higher mileage day however, it is most enjoyable. We'll rise early and pack, then fuel in Spray. Lunch will come in Crescent where we will fuel for the trip home. The Crater Lake Hwy highlights our return home!

Mileage: Crooked River Canyon 221 mi.

Campground: Chimney Rock, Palisades, Cobble Rock, Still Water.

Info: The section of river flows through scenic vertical basalt canyons and is like dropping into another world!

DAY 2 Central Oregon, Malheur, Strawberries, Eldorado Camp.

Mileage: Center of Oregon Strawberries, Elderado C.G.. 208 mi.

Campground: Eldorado

Info: This segment is Scenic, Historical, Curvy, and incorporates wide open view of pristine cattle country. It truly is the center of Oregon.

DAY 3 Burnt Canyon, Deer Camp.

Mileage: Burnt Canyon Deer Camp 139 mi.

Campground: Deerhorn Campground

Info: This small campground offers fishing, exploring, nature watching and hunting opportunities in the Middle Fork John Day River State Scenic Waterway. The campground is busiest during late summer and hunting season. It provides a very fun road adventure on the next day on County Road 20

DAY 4 Umatilla National Forest to Spray

Mileage: The Umatilla to Spray. 165 mi.

Campground: Spray Riverfront Park

Info: A year after Wheeler County, Oregon was officially formed in 1900, John and Mary Spray established a post office on the banks of the John Day River. Over a century later, Spray's settlement is barely even a town, boasting just a few general stores and a gas station. But therein lies Spray's charm: the escape from development. This little town of fewer than 200 residents hosts a quaint and surprisingly full-service community park, however. No doubt the park's main attraction is its access to the John Day River, whether for floating, fishing, or taking a swim on a hot, dry summer day. The park also features restrooms, a large picnic shelter, and six first-come, first-served walk-in tent campsites. The campsites are $12 per night, and a $5 fee is charged for boat launches.

DAY 5 Painted Hills and Fossil Lands

Mileage: The Painted Fossil Stuff! 235 mi.

Campground: Spray Riverfront Park

Info: No packing up to move today! This is a ride day after a little breakfast in town!

DAY 6 Home

Mileage: Home. 321 mi

Campground: Your Place!

Info: The ride from Spray is a higher mileage day however, it is most enjoyable. We'll rise early and pack, then fuel in Spray. Lunch will come in Crescent where we will fuel for the trip home. The Crater Lake Hwy highlights our return home!

HISTORY AND INFORMATION

The Crooked River

The Crooked River is noted for its ruggedly beautiful scenery, outstanding whitewater boating and a renowned sport fishery for steelhead, brown trout and native rainbow trout. Located in central Oregon, it offers excellent hiking opportunities with spectacular geologic formations and waterfalls. A portion of the designated segment provides expert class IV-V kayaking/rafting during spring runoff. The section of river from the Ochoco National Forest to Opal Springs flows through scenic vertical basalt canyons. The Chimney Rock segment is becoming increasingly popular for the accessibility of outdoor activities

Botanic & Ecologic

In addition to supporting a wide variety of botanical resources, the Crooked River possesses a unique stand of mature white alder/red-osier dogwood in an area that is in near-pristine condition and is also suspected to contain of Estes' wormwood.

Geologic

Fifty million years of geologic history are dramatically displayed on the canyon walls of the Crooked River. Volcanic eruptions which occurred over thousands of years created a large basin dramatized by colorful layers of basalt, ash and sedimentary formations. The most significant contributor to the outstandingly remarkable geologic resource are the unique intra-canyon basalt formations created by recurring volcanic and hydrologic activities.

Hydrologic

Water from springs and stability of flows through the steep basalt canyon section of the Crooked River has created a stream habitat and riparian zone that is extremely stable and diverse, unique in a dry semi-arid climate environment. Features, such as Odin, Big and Steelhead Falls; springs and seeps; white water rapids; water sculpted rock; and the river canyons, are very prominent and represent excellent examples of hydrologic activity within central Oregon.

Recreational

The Crooked offers a diversity of year-round recreation opportunities, such as fishing, hiking, backpacking, camping, wildlife and nature observation, whitewater boating, picnicking, swimming, hunting and photography. The Chimney Rock segment is popular for camping, fishing, hiking, bicycling and for viewing eagles, ospreys and other wildlife. The 2.6-mile (round trip) hike to Chimney Rock rewards visitors with expansive views of the Crooked River Canyon and Cascades. The lower section offers a semi-primitive experience due to its remoteness, and a portion of the river is noted for high quality class IV-V whitewater paddling.

Scenic

The exceptional scenic quality along the Crooked River is due to the rugged natural character of the canyons, outstanding scenic vistas, limited visual intrusions and scenic diversity resulting from a variety of geologic formations, vegetation communities and dynamic river characteristics. State Scenic Highway 27, a designated National Back Country Byway, offers views of western juniper decorating the steep hillsides, spectacular geologic formations and eroded lava flows throughout the narrow, winding canyon corridor.

Wildlife

The river supports critical mule deer winter range habitat and nesting/hunting habitat for bald eagles, golden eagles, ospreys and other raptors. Bald eagles are known to winter within the Crooked River segment and along the Deschutes River downriver from the Lower Bridge. Outstanding habitat areas include high vertical cliffs, wide talus slopes, numerous caves, pristine riparian zones and extensive grass/sage covered slopes and plateaus.

The Crooked River is noted for its ruggedly beautiful scenery, outstanding whitewater boating and a renowned sport fishery for steelhead, brown trout and native rainbow trout. Located in central Oregon, it offers excellent hiking opportunities with spectacular geologic formations and waterfalls. A portion of the designated segment provides expert class IV-V kayaking/rafting during spring runoff. The section of river from the Ochoco National Forest to Opal Springs flows through scenic vertical basalt canyons. The Chimney Rock segment is becoming increasingly popular for the accessibility of outdoor activities

Botanic & Ecologic

In addition to supporting a wide variety of botanical resources, the Crooked River possesses a unique stand of mature white alder/red-osier dogwood in an area that is in near-pristine condition and is also suspected to contain of Estes' wormwood.

Geologic

Fifty million years of geologic history are dramatically displayed on the canyon walls of the Crooked River. Volcanic eruptions which occurred over thousands of years created a large basin dramatized by colorful layers of basalt, ash and sedimentary formations. The most significant contributor to the outstandingly remarkable geologic resource are the unique intra-canyon basalt formations created by recurring volcanic and hydrologic activities.

Hydrologic

Water from springs and stability of flows through the steep basalt canyon section of the Crooked River has created a stream habitat and riparian zone that is extremely stable and diverse, unique in a dry semi-arid climate environment. Features, such as Odin, Big and Steelhead Falls; springs and seeps; white water rapids; water sculpted rock; and the river canyons, are very prominent and represent excellent examples of hydrologic activity within central Oregon.

Recreational

The Crooked offers a diversity of year-round recreation opportunities, such as fishing, hiking, backpacking, camping, wildlife and nature observation, whitewater boating, picnicking, swimming, hunting and photography. The Chimney Rock segment is popular for camping, fishing, hiking, bicycling and for viewing eagles, ospreys and other wildlife. The 2.6-mile (round trip) hike to Chimney Rock rewards visitors with expansive views of the Crooked River Canyon and Cascades. The lower section offers a semi-primitive experience due to its remoteness, and a portion of the river is noted for high quality class IV-V whitewater paddling.

Scenic

The exceptional scenic quality along the Crooked River is due to the rugged natural character of the canyons, outstanding scenic vistas, limited visual intrusions and scenic diversity resulting from a variety of geologic formations, vegetation communities and dynamic river characteristics. State Scenic Highway 27, a designated National Back Country Byway, offers views of western juniper decorating the steep hillsides, spectacular geologic formations and eroded lava flows throughout the narrow, winding canyon corridor.

Wildlife

The river supports critical mule deer winter range habitat and nesting/hunting habitat for bald eagles, golden eagles, ospreys and other raptors. Bald eagles are known to winter within the Crooked River segment and along the Deschutes River downriver from the Lower Bridge. Outstanding habitat areas include high vertical cliffs, wide talus slopes, numerous caves, pristine riparian zones and extensive grass/sage covered slopes and plateaus.

Central Oregon, Malheur, Strawberries, Eldorado Camp.

Paulina

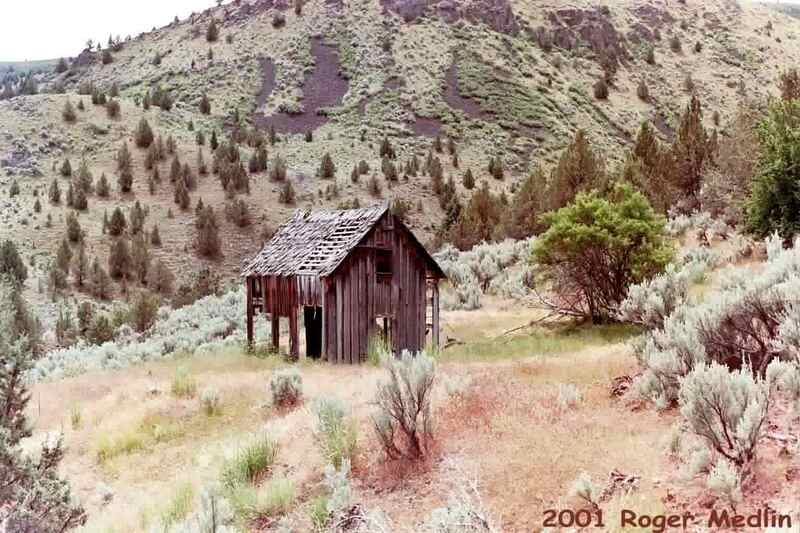

Named after Paiute Chief Paulina, the community was founded in 1870. The post office was established in 1880 by John Faulkner who served for 25 years. The first store was built in 1905 but burned in 1929. Both a hotel and a clubhouse and saloon were constructed in 1906. The current store was built in 1917. At one time, Paulina had two active sawmills. Today, the mills are gone and so too are most of the businesses. The ranches are bigger and both the towering irrigation systems and the modern equipment make it clear that progress has found its way to the high desert. A number of historic buildings still stand in Paulina and there are plenty of old one-room schoolhouses in the countryside, reminders that eastern Crook County has a long and proud history.

Izee

IZ Cattle Ranch is located in the town of Izee, Oregon, a small outpost along the South Fork of the John Day River about twenty miles east of Paulina. The lush grassland along the South Fork of the John Day river made this land a popular grazing location for cattle and sheep herders in the late 1800s. A ranching boom began in the 1880s and the unique name Izee was born quite spontaneously when the growing population forced the need for a Post Office in the boom-town. A local homesteader and former cavalry man, Carlos Bonham, named the town after his own cattle brand “IZ” when he applied for a postal code as the town’s first postmaster.

The Malheur

Like all National Forests, the Malheur belongs to all Americans and is managed under the multiple-use principle "for the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run." The diverse and beautiful scenery of the forest includes high desert grasslands, sage and juniper, pine, fir and other tree species, and the hidden gems of alpine lakes and meadows. Elevations vary from about 4000 feet (1200 meters) to the 9038 foot (2754 meters) top of Strawberry Mountain. The Strawberry Mountain range extends east to west through the center of the Forest. For many years, these forested lands have been important to the people who live here. Native Americans hunted game, gathered roots and berries, and traded and socialized with each other sustaining their lives and cultures. These lands are still important to them. As explorers, fur trappers, and gold miners discovered this area, the forest and its many resources played an important role in the development of local communities, a role that continues today.

The Monument Rock Wilderness

Located at the southernmost edge of the Blue Mountains and along the eastern edge of the Strawberry Mountain range. The area was established by Congress in 1984 as part of the Oregon Wilderness Act. Encompassing 20,079 acres this wilderness spans the Malheur and Wallowa-Whitman National Forests. Offering views across much of northeastern Oregon, elevations ranges from 5,200 feet in the lower slopes to 7,815 feet atop Table Rock. The northern end of the area lies across a watershed divide that separates the headwaters of the Little Malheur River and the upper drainage of the South Fork Burnt River. The wilderness is mostly forested with ponderosa pine in lower hills stretching up to subalpine fir along the peaks. Other tree species include lodgepole pine, Douglas-fir, white fir, aspen, and juniper. Intermingled amongst the pine-fir forests and riparian stream bottoms are native grasslands with bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue and other indigenous grasses. Throughout the area is diversity of wildlife habitat for species such as mule deer, Rocky Mountain elk, badgers, and the rare wolverine. There are 70 species of birds living here, including the creek-loving American dipper and the pileated woodpecker. Soils in the area are predominantly volcanic ash, and rocks that are mostly lavas poured out over the land.

Paulina

Named after Paiute Chief Paulina, the community was founded in 1870. The post office was established in 1880 by John Faulkner who served for 25 years. The first store was built in 1905 but burned in 1929. Both a hotel and a clubhouse and saloon were constructed in 1906. The current store was built in 1917. At one time, Paulina had two active sawmills. Today, the mills are gone and so too are most of the businesses. The ranches are bigger and both the towering irrigation systems and the modern equipment make it clear that progress has found its way to the high desert. A number of historic buildings still stand in Paulina and there are plenty of old one-room schoolhouses in the countryside, reminders that eastern Crook County has a long and proud history.

Izee

IZ Cattle Ranch is located in the town of Izee, Oregon, a small outpost along the South Fork of the John Day River about twenty miles east of Paulina. The lush grassland along the South Fork of the John Day river made this land a popular grazing location for cattle and sheep herders in the late 1800s. A ranching boom began in the 1880s and the unique name Izee was born quite spontaneously when the growing population forced the need for a Post Office in the boom-town. A local homesteader and former cavalry man, Carlos Bonham, named the town after his own cattle brand “IZ” when he applied for a postal code as the town’s first postmaster.

The Malheur

Like all National Forests, the Malheur belongs to all Americans and is managed under the multiple-use principle "for the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run." The diverse and beautiful scenery of the forest includes high desert grasslands, sage and juniper, pine, fir and other tree species, and the hidden gems of alpine lakes and meadows. Elevations vary from about 4000 feet (1200 meters) to the 9038 foot (2754 meters) top of Strawberry Mountain. The Strawberry Mountain range extends east to west through the center of the Forest. For many years, these forested lands have been important to the people who live here. Native Americans hunted game, gathered roots and berries, and traded and socialized with each other sustaining their lives and cultures. These lands are still important to them. As explorers, fur trappers, and gold miners discovered this area, the forest and its many resources played an important role in the development of local communities, a role that continues today.

The Monument Rock Wilderness

Located at the southernmost edge of the Blue Mountains and along the eastern edge of the Strawberry Mountain range. The area was established by Congress in 1984 as part of the Oregon Wilderness Act. Encompassing 20,079 acres this wilderness spans the Malheur and Wallowa-Whitman National Forests. Offering views across much of northeastern Oregon, elevations ranges from 5,200 feet in the lower slopes to 7,815 feet atop Table Rock. The northern end of the area lies across a watershed divide that separates the headwaters of the Little Malheur River and the upper drainage of the South Fork Burnt River. The wilderness is mostly forested with ponderosa pine in lower hills stretching up to subalpine fir along the peaks. Other tree species include lodgepole pine, Douglas-fir, white fir, aspen, and juniper. Intermingled amongst the pine-fir forests and riparian stream bottoms are native grasslands with bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue and other indigenous grasses. Throughout the area is diversity of wildlife habitat for species such as mule deer, Rocky Mountain elk, badgers, and the rare wolverine. There are 70 species of birds living here, including the creek-loving American dipper and the pileated woodpecker. Soils in the area are predominantly volcanic ash, and rocks that are mostly lavas poured out over the land.

Burnt Canyon, Durkee, Deer Camp.

From the West one enters the Oregon Trail through the Burnt River Canyon. It is both wild and scenic, offering great opportunities for viewing Big Horn Sheep. It has been said, If Baker County is a microcosm of Western development, the Durkee valley is a postage stamp sized microcosm. It enfolds the story of the West; from the Indian trail to Oregon Trail to cattle to Transcontinental railroads and highway to modern industry, just across the fence. The Oregon Trail proceeded up the Burnt River, where the way was rocky, rough, and ruinous to pioneer stock and wagons. It should cause no wonder that pioneers often took to the hills above the Burnt River Canyon wherever possible. One such diversion was the trail up Sisley Creek and down Swazey to elude the grasp of the canyon near Nelson Point, but yet to enter the luxurious little Durkee valley.

From Unity, the South and North Fork of the River merge. From this point at the upper end of the valley Burnt River tumbled from its brawling passage through the now rural farm communities of Hereford and Bridgeport into the Burnt River Canyon. Here it flowed through a pioneer paradise with lush green pasture, level ground, and a place to rest after the grueling pull from Farewell Bend on the Snake River and over the mountain range between there and Durkee. It was first named Express until later named Durkee. It was natural that sheep and cattlemen should see these valley's as desirable for ranching. This range situated to the east a dozen miles is the Lookout mountain range. It was used by Indians as a key Lookout and by ranchers as sheep and cattle range. It was also the first place that I cracked 3 ribs on an Adventure Bike! To the south is the Pedro mountain range, Morman Basin and Rye Valley. To the northeast is the saddle between Burnt and Powder River drainages. In 1880-1884, the railroad sought this route. Durkee prospered as a construction and maintenance area. Attempting to avoid the Burnt River Canyon, one branch of the Oregon Trail passed through the high mountain placer country known as Rye Valley and dropped into the lower end of Durkee valley. Durkee has retained its "home" atmosphere of family ranches, had its school, Grange, Village Store and Church, and a blacksmith shop.The Ash Grove Cement West, Inc. plant, (formerly Oregon-Portland Cement), is one of Baker County's largest industries.

From the West one enters the Oregon Trail through the Burnt River Canyon. It is both wild and scenic, offering great opportunities for viewing Big Horn Sheep. It has been said, If Baker County is a microcosm of Western development, the Durkee valley is a postage stamp sized microcosm. It enfolds the story of the West; from the Indian trail to Oregon Trail to cattle to Transcontinental railroads and highway to modern industry, just across the fence. The Oregon Trail proceeded up the Burnt River, where the way was rocky, rough, and ruinous to pioneer stock and wagons. It should cause no wonder that pioneers often took to the hills above the Burnt River Canyon wherever possible. One such diversion was the trail up Sisley Creek and down Swazey to elude the grasp of the canyon near Nelson Point, but yet to enter the luxurious little Durkee valley.

From Unity, the South and North Fork of the River merge. From this point at the upper end of the valley Burnt River tumbled from its brawling passage through the now rural farm communities of Hereford and Bridgeport into the Burnt River Canyon. Here it flowed through a pioneer paradise with lush green pasture, level ground, and a place to rest after the grueling pull from Farewell Bend on the Snake River and over the mountain range between there and Durkee. It was first named Express until later named Durkee. It was natural that sheep and cattlemen should see these valley's as desirable for ranching. This range situated to the east a dozen miles is the Lookout mountain range. It was used by Indians as a key Lookout and by ranchers as sheep and cattle range. It was also the first place that I cracked 3 ribs on an Adventure Bike! To the south is the Pedro mountain range, Morman Basin and Rye Valley. To the northeast is the saddle between Burnt and Powder River drainages. In 1880-1884, the railroad sought this route. Durkee prospered as a construction and maintenance area. Attempting to avoid the Burnt River Canyon, one branch of the Oregon Trail passed through the high mountain placer country known as Rye Valley and dropped into the lower end of Durkee valley. Durkee has retained its "home" atmosphere of family ranches, had its school, Grange, Village Store and Church, and a blacksmith shop.The Ash Grove Cement West, Inc. plant, (formerly Oregon-Portland Cement), is one of Baker County's largest industries.

The Umatilla to Spray

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UMATILLA NATIONAL FOREST

1804-1806

The Lewis and Clark Expedition ventured close to the north and west sides of the Umatilla National Forest as they traveled along the Snake and Columbia rivers. As the Lewis & Clark party drew closer to the Walla Walla River on their return trip in 1806, their journal entries note the absence of firewood, Indian use of shrubs for fuel, abundant roots for human consumption, and good availability of grass for horses. Writing some distance up the Walla Walla River, William Clark noted that “great portions of these bottoms has been latterly burnt which has entirely destroyed the timbered growth” (Robbins 1997).

1810-1840

This 3-decade period was a period of exploration and use by trappers, missionaries, naturalists, and government scientists or explorers. William Price Hunt (fur trader), John Kirk Townsend (naturalist), Peter Skene Ogden (trapper and guide), Thomas Nuttall (botanist), Reverend Samuel Parker (missionary), Marcus and Narcissa Whitman (missionaries), Henry and Eliza Spaulding (missionaries), Captain Benjamin Bonneville (military explorer), Captain John Charles Fremont (military scientist),

Nathaniel J. Wyeth (fur trader), and Jason Lee (missionary) are just a few of the people who visited and described the Blue Mountains during this era.

1840-1859

During the 1840s and 1850s – the Oregon Trail era – much overland migration occurred as settlers passed through the Blue Mountains on their way to the Willamette Valley (the Oregon Trail continued to receive fairly heavy use until well into the late 1870s). The Oregon Trail traversed the Umatilla National Forest. In 1847, Cayuse Indians attacked the Whitman Mission, which had been established in 1838 near the present location of Walla Walla, and this attack unleashed a war between American Indians and Euro-American emigrants in the Columbia River basin. In August of 1848, at least partly in response to the Cayuse War, the U.S. Congress created a very large Oregon Territory (containing at least three existing states). In 1853, the Washington Territory was split off from the larger Oregon Territory, followed by the Idaho Territory in 1863. In June of 1855, treaties were ratified with the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla, Yakima, and Nez Perce tribes. The Umatilla National Forest contains ceded lands from all of these tribes. [Ceded lands have reserved Indian rights for fishing, hunting, gathering roots and other traditional foodstuffs, and pasturing of livestock. In the mid 1850s, a large forest fire (about 88,000 acres) came from the present Umatilla Indian Reservation, burned up the Umatilla River, into the Wenaha Forest Reserve, then turned north along the west slope across the heads of the Walla Wallas, and reached as far as the head of the Wenaha River.

1860s

The 1860s was a primary settlement period for much of the Umatilla National Forest because Oregon Trail emigrants (see the 1840-1859 section) were passing through on their way to western Oregon, so little Blue Mountains settlement occurred then. In the early 1860s, gold was discovered in the Blue Mountains, eventually leading to hydraulic dredge mining on the southern part of the Umatilla National Forest. Early gold finds were primarily surface deposits and these placer lodes were seldom sustained long. In the fall of 1863, an Oregon farmer sowed 50 acres of wheat on non-irrigated uplands near Weston, and eventually harvested 35 bushels per acre by late in the following summer. Wheat farming, which was highly dependent on human and animal labor, quickly had a major impact on livestock numbers because many draft horses were needed to pull wheat plowing and harvesting equipment. Passage of the 1862 Homestead Act established a process for emigrants to obtain up to 160 acres of public lands for free, providing they paid a modest filing fee and met the terms of proof (built a dwelling, proved agricultural viability, etc.). The Umatilla National Forest included many homestead claims. In 1867, a General Land Office was established in La Grande to initiate public land surveys in the Blue Mountains, and to process homestead applications.

1870s

The General Land Office surveyed lands within the Umatilla National Forest between 1863 and the mid 1930s, but most of the Forest was initially surveyed between 1879 and 1887.

1880s

The Oregon Short Line Railroad was built in the mid 1880s in a southeasterly direction from Wallula, Washington to Huntington, Oregon, where it connected with Union Pacific’s main line. This was the first major railroad line to traverse the Blue Mountains, and it became an important transportation corridor for the Umatilla National Forest.

1890s

During the 1890s, sheep grazing on the Umatilla National Forest began escalating to very high numbers, with much of the wool being used by the Pendleton Woolen Mills to manufacture a wide range of wool blankets and other articles. Large roving bands of sheep on the open range (non-reserved public domain lands) led to

range wars between cattle and sheep operators, with bloodshed occurring in some areas.

1900s

Between 1904 and 1907, many public domain lands were formally withdrawn as Forest Reserves for the Blue Mountains region: Wenaha (northern Umatilla NF) in 1905; Heppner and Blue Mountains (southern Umatilla NF) in 1906. The forest reserves were intended to conserve the area’s water supply for farmers, reduce

conflict between stockmen, and to protect timberlands and summer rangelands from “destruction and wasteful use.” In 1905, just prior to establishment of the Wenaha Forest Reserve, the northern half of the Umatilla National Forest supported somewhere in excess of 275,000 head of grown sheep plus their increase, 40,000 head of cattle, and 15,000 head of horses. All these animals grazed annually on what is now the Pomeroy and Walla Walla Ranger Districts. 1905 was considered to represent a low point for big-game animals (elk and deer) on the Umatilla National Forest. After the Forest was established in 1908, wild game increased steadily: 1938 estimates put the populations at about 10,000 deer and 7,000 elk. In 1906, the open-range wars ended when the U.S. Forest Service began regulating use of summer range by allotting separate areas of the forest reserves to cattle and sheep (and by not allowing the two stock classes to intermingle on the same range). In 1907, Representative Charles Fulton of Oregon introduced an amendment in the U.S. Congress to prohibit further Forest Reserve withdrawals in the Pacific Northwest. Before

this law went into effect, President Theodore Roosevelt created his famous “midnight reserves” by setting aside 16 million acres, including the Blue Mountains, Colville, and Imnaha forest reserves. In 1908, the Heppner, Umatilla, Wenaha, and Whitman national forests were established by Presidential executive order (all of these forests contained lands now included within the Umatilla National Forest boundary). Umatilla National Forest established by proclamation on June 13, 1908.

1910s

As was the case for much of the western United States, the Umatilla National Forest experienced very high levels of forest fire activity in 1910 – more than 97,000 acres burned, a greater acreage than was recorded for any other year in the Forest’s history. In the second half of the 1910s, a large outbreak of mountain pine beetle occurred across the Blue Mountains; the first insect-control project in the country occurred in 1910 when $5,000 was diverted from the nation’s firefighting account to combat beetle damage in northeastern Oregon. In 1915, a Forest Supervisor’s office for the Umatilla National Forest was established at Pendleton in the Post Office building, having been moved there from Heppner. Elk were transplanted to the Wenaha National Forest and the northern Blue Mountains in February 1913 (Pomeroy area), March 1913 (Walla Walla area), winter of 1918 (Blue Mountains near Walla Walla), and January 1930 (south of Dayton, WA). The source of

these transplanted elk was Montana.

1920s

In November 1920, the Wenaha National Forest (containing lands now administered by the Pomeroy and Walla Walla Ranger Districts) was combined with the Umatilla National Forest to the south, and the combined unit was called the Umatilla National Forest.

1930s

In 1935, U.S. Highway 395 was completed as a paved road. This highway is a major north-south transportation corridor for the southern half of the Umatilla National Forest, and for the remainder of the central and southern Blue Mountains. Late in 1937, the Camas Creek timber sale was awarded to the Milton Box Company of Milton, Oregon. This was the largest timber sale ever awarded on the Umatilla National Forest: 221.3 million board feet. Throughout the 1930s, much work was accomplished on the Umatilla National Forest by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a “New Deal” initiative instituted during the Great Depression by the Franklin D. Roosevelt presidential administration. Fire fighting, trail construction, recreation site development, tree planting, building construction, range improvements, precommercial thinning, and a variety of other work was accomplished by the CCC. The Umatilla National Forest had CCC camps at Ukiah, Bingham Springs (on the

Umatilla River), Wilson Prairie (Heppner), near Pomeroy, and at several other locations. The 4-mile road from Tollgate to Target Meadows, where soldiers from Fort Walla Walla went each summer for gunnery practice, was completed by CCC crews. In the late 1930s, the Blue Mountain Ski Club continued developing a winter sports playground called the Lookingglass Creek bowl near Tollgate. Ski lift planning commenced in August of 1938 for what would eventually become the Spout Springs ski area.

1940s

The Harris Pine Mills timber processing plant opened in Pendleton in May of 1940. Much of the timber removed from the Camas Creek timber sale area (located on the North Fork John Day Ranger District) was processed into wood products (fruit shipping boxes, furniture, lumber, etc.) by the Harris Pine Company. Beginning in the early 1940s, national forest tree harvests increased to meet a heightened demand for wood products during World War II, and to provide raw materials for new housing after the war. Annual harvest levels reached 39 million board feet on the Umatilla National Forest in 1944 (cut volume). What is now the Tollgate Work Center opened as a Ranger District office in late summer or fall of 1941, just before District Ranger Albert Baker retired in December of 1941. During this era, Walla Walla was an “in-and-out” district because it had two offices: one at Walla Walla as the winter headquarters, and another at Tollgate as the summer office. From 1944 to 1958, a huge outbreak of western spruce budworm affected the entire Blue Mountains, with almost 900,000 acres of the Umatilla National Forest affected in 1950. From 1945 to 1947, a localized outbreak of Douglas-fir tussock moth occurred on the northern Umatilla National Forest near Troy, Oregon; 14,000 acres of the infested area were sprayed with an insecticide called DDT in June of 1947.

1950s

Spray projects were completed on portions of the Umatilla National Forest in 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1958. During these projects, an insecticide called DDT was applied from aircraft to suppress western spruce budworm populations. Timber harvesting on Blue Mountains national forests began in earnest in the mid 1950s,

when most sales were partial cuts where only the most valuable trees were removed. On the Umatilla National Forest, annual timber harvest levels reached 89 million board feet by 1959 (cut volume). On September 17, 1950, a ceremony was held at Big Saddle, near Table Rock lookout, to dedicate the Kendall Skyline Road. This road was named in honor of William H. Kendall, an early District Ranger (prior to 1920) who was instrumental in the road’s conception and development. Although private funds built the first few miles of this road during World War I, federal funds ultimately constructed most of it, including countless hours by CCC work crews during the mid 1930s. At one point, the Walla Walla CCC camp included 216 young men, many of whom spent time on road projects such as the Kendall Skyline Road.

1960s

By the mid 1960s, small timber sales were made on the north end of the Umatilla National Forest (Abels Ridge and other areas on Pomeroy RD; Swamp Creek and other areas on Walla Walla RD). These early clearcuts now support vigorous, second-growth stands of mixed conifers, and many of them have been thinned several times since the 1970s. In 1968, two research natural areas were designated on the Umatilla National Forest, both of which are located on the Pomeroy Ranger District: Pataha Bunchgrass RNA in Garfield County, and Rainbow Creek RNA in Columbia County. In the late 1960s, a 55-foot-tall dam (about 350 feet long) was developed along Mottet Creek to create Jubilee Lake on the Walla Walla Ranger District. The lake was dedicated on June 1, 1968. The lake area had long been considered for an impoundment; the first US Forest Service site survey occurred in the 1930s. Like Bull Prairie Lake on the Heppner RD, Jubilee Lake development was financed by the Oregon Game Commission using funds generated from fishing license fees. Jubilee Lake covers about 100 acres (second

only in size to Olive Lake on the Umatilla NF), and it is a major recreation attraction.

1970s

Between 1972 and 1974, the northern Blue Mountains experienced the largest outbreak of Douglas-fir tussock moth ever recorded anywhere in North America. The Forest Service eventually convinced the Environmental Protection Agency to temporarily suspend their 1972 ban of DDT so it could be used against tussock moth; more than 426,000 acres were sprayed with DDT in a tri-State area in 1974, with only 32,700 of the sprayed acres located on the Umatilla National Forest. In the mid and late 1970s, many salvage timber sales were completed to remove trees killed or damaged by Douglas-fir tussock moth defoliation. About 137 million board feet of

timber was salvaged from tussock-moth areas on the Pendleton Ranger District alone. In the mid 1970s, a very large mountain pine beetle outbreak occurred in lodgepole pine forests throughout the central and southern portions of the Blue Mountains – more than 375,000 acres of the Umatilla National Forest were affected in 1976.

In 1972, four management treatments were installed at the High Ridge Barometer Watershed – large clearcuts, small clearcuts, selective cutting, and an untreated (control) area. The High Ridge study was initially established in October of 1967 to document weather

conditions for a high-elevation watershed, and to monitor water flow and sediment production changes associated with timber production practices. In the early 1970s, the upper portion of the Tiger Creek (Tiger Canyon) road was developed, with initial work commencing in July of 1971. This is a major recreational road and access point to the Umatilla National Forest for residents of Walla Walla, Washington. The Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness was created by passage of the Endangered American

Wilderness Act of 1978.

1980s

On January 15, 1980, nearly 2,000 skiers flocked to the opening of the Bluewood Ski Area located 23 miles south of Dayton, Washington. In October of 1980, the Woodland Sno-Park site, located about 2 miles south of the Spout Springs ski area and adjacent to Oregon Highway 204, was completed and opened. Like other snow parks, this project was developed cooperatively by a state’s Department of Transportation, Boise Cascade Corporation, and a local snowmobile club. From the late 1970s to the late 1980s, very high levels of timber harvesting occurred on Blue Mountain national forests. On the Umatilla National Forest, annual harvest levels

reached 222 million board feet in 1973, and 227 million board feet in 1989 (cut volume). Beginning in 1980 and continuing until 1992, a large outbreak of western spruce budworm affected the Umatilla National Forest (and the remainder of the Blue Mountains). Several suppression (spray) projects occurred during this outbreak, when either chemical or biological control agents were applied from aircraft. In 1984, two new Wilderness areas were designated on the Umatilla National Forest: North Fork John Day Wilderness (located on the North Fork John Day Ranger District), and the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness (located on the Walla Walla Ranger District). In the early 1980s, the Umatilla National Forest installed the Data General computer system. This “DG system” represented the first agency-wide implementation of standardized technology throughout all levels and offices of the U.S. Forest Service.

1990s

In 1990, the first comprehensive Land and Resource Management Plan was approved for the Umatilla National Forest. It replaced a group of so-called “unit plans,” all of which were prepared and approved in the 1970s, covering smaller portions of the Forest. The 1990 Forest Plan established management direction for a 10-year implementation period (at most 15 years), but it is still in place today. In April 1991, the Blue Mountains Forest Health Report was released. This report described deteriorating forest health conditions on the Umatilla National Forest (and the remainder of the Blue Mountains). Between 1992 and 1994, several broad-scale reports pertaining to the Umatilla National Forest were released. The Caraher Report was issued in July 1992. A draft version of the Everett Report was released in April 1993, with the final report produced in 1994. The Eastside Forests Scientific Society Panel report was published in August 1994. The Eastside Screens were issued in August 1993 in response to a petition and threatened lawsuit from the Natural Resources Defense Council. The Screens established interim direction that all timber sale projects are required to meet. Following a lawsuit filed by Prairie Wood Products, the Eastside Screens were required to meet NEPA requirements by amending the Umatilla Forest Plan. The Screens are still in force today. In March 1994, interim strategies for managing anadromous fish-producing watersheds in

eastern Oregon and Washington, Idaho, and portions of California sued. This interim direction is geared toward restoration of aquatic habitat and riparian areas on lands administered by the Forest Service and BLM; PACFISH is still in force today. On January 21, 1994, the Chief of the Forest Service and the Director of the USDI Bureau of Land Management signed a charter establishing the Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project (ICBEMP). This project resulted in broad- and mid-scale scientific assessments covering more than 144 million acres (76 million of which are federal) in seven western states. Although the environmental impact statement that would have amended the Umatilla Forest Plan was never completed, the ICBEMP effort still produced a wealth of scientific information that continues to influence management of the Umatilla National Forest today. In 1996, a large amount of wildfire activity occurred on the southern half of the Umatilla National Forest, with the Wheeler Point (Heppner RD), Tower, Bull, and Summit (North Fork John Day RD) fires affecting more than 72,000 acres of national forest lands. During the 1990s, timber harvest levels declined dramatically; recent timber harvest levels for the Umatilla National Forest (from the mid 1990s to the present) are the lowest they have been since the mid 1950s.

2000s

Late in the 1990s, a long-term nemesis of the Umatilla National Forest – Douglas-fir tussock moth – once again reached outbreak status, and more than 39,000 acres were sprayed with a natural virus in June and July of 2000 to minimize defoliation damage. In the mid 2000s, several very large forest fires occurred on the Umatilla National Forest, with the School Fire burning about 28,000 acres of National Forest System lands in 2005 (Pomeroy Ranger District), the Columbia Complex Fire affecting about 50,000 acres in 2006 (Pomeroy and Walla Walla Ranger Districts), and the Monument Complex Fire covering about 19,800 acres (Heppner Ranger District). In the late 2000s, moose numbers on the Umatilla National Forest increased to the point where they were no longer considered a transient animal, and it is now assumed that a resident population has gotten established.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UMATILLA NATIONAL FOREST

1804-1806

The Lewis and Clark Expedition ventured close to the north and west sides of the Umatilla National Forest as they traveled along the Snake and Columbia rivers. As the Lewis & Clark party drew closer to the Walla Walla River on their return trip in 1806, their journal entries note the absence of firewood, Indian use of shrubs for fuel, abundant roots for human consumption, and good availability of grass for horses. Writing some distance up the Walla Walla River, William Clark noted that “great portions of these bottoms has been latterly burnt which has entirely destroyed the timbered growth” (Robbins 1997).

1810-1840

This 3-decade period was a period of exploration and use by trappers, missionaries, naturalists, and government scientists or explorers. William Price Hunt (fur trader), John Kirk Townsend (naturalist), Peter Skene Ogden (trapper and guide), Thomas Nuttall (botanist), Reverend Samuel Parker (missionary), Marcus and Narcissa Whitman (missionaries), Henry and Eliza Spaulding (missionaries), Captain Benjamin Bonneville (military explorer), Captain John Charles Fremont (military scientist),

Nathaniel J. Wyeth (fur trader), and Jason Lee (missionary) are just a few of the people who visited and described the Blue Mountains during this era.

1840-1859

During the 1840s and 1850s – the Oregon Trail era – much overland migration occurred as settlers passed through the Blue Mountains on their way to the Willamette Valley (the Oregon Trail continued to receive fairly heavy use until well into the late 1870s). The Oregon Trail traversed the Umatilla National Forest. In 1847, Cayuse Indians attacked the Whitman Mission, which had been established in 1838 near the present location of Walla Walla, and this attack unleashed a war between American Indians and Euro-American emigrants in the Columbia River basin. In August of 1848, at least partly in response to the Cayuse War, the U.S. Congress created a very large Oregon Territory (containing at least three existing states). In 1853, the Washington Territory was split off from the larger Oregon Territory, followed by the Idaho Territory in 1863. In June of 1855, treaties were ratified with the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla, Yakima, and Nez Perce tribes. The Umatilla National Forest contains ceded lands from all of these tribes. [Ceded lands have reserved Indian rights for fishing, hunting, gathering roots and other traditional foodstuffs, and pasturing of livestock. In the mid 1850s, a large forest fire (about 88,000 acres) came from the present Umatilla Indian Reservation, burned up the Umatilla River, into the Wenaha Forest Reserve, then turned north along the west slope across the heads of the Walla Wallas, and reached as far as the head of the Wenaha River.

1860s

The 1860s was a primary settlement period for much of the Umatilla National Forest because Oregon Trail emigrants (see the 1840-1859 section) were passing through on their way to western Oregon, so little Blue Mountains settlement occurred then. In the early 1860s, gold was discovered in the Blue Mountains, eventually leading to hydraulic dredge mining on the southern part of the Umatilla National Forest. Early gold finds were primarily surface deposits and these placer lodes were seldom sustained long. In the fall of 1863, an Oregon farmer sowed 50 acres of wheat on non-irrigated uplands near Weston, and eventually harvested 35 bushels per acre by late in the following summer. Wheat farming, which was highly dependent on human and animal labor, quickly had a major impact on livestock numbers because many draft horses were needed to pull wheat plowing and harvesting equipment. Passage of the 1862 Homestead Act established a process for emigrants to obtain up to 160 acres of public lands for free, providing they paid a modest filing fee and met the terms of proof (built a dwelling, proved agricultural viability, etc.). The Umatilla National Forest included many homestead claims. In 1867, a General Land Office was established in La Grande to initiate public land surveys in the Blue Mountains, and to process homestead applications.

1870s

The General Land Office surveyed lands within the Umatilla National Forest between 1863 and the mid 1930s, but most of the Forest was initially surveyed between 1879 and 1887.

1880s

The Oregon Short Line Railroad was built in the mid 1880s in a southeasterly direction from Wallula, Washington to Huntington, Oregon, where it connected with Union Pacific’s main line. This was the first major railroad line to traverse the Blue Mountains, and it became an important transportation corridor for the Umatilla National Forest.

1890s

During the 1890s, sheep grazing on the Umatilla National Forest began escalating to very high numbers, with much of the wool being used by the Pendleton Woolen Mills to manufacture a wide range of wool blankets and other articles. Large roving bands of sheep on the open range (non-reserved public domain lands) led to

range wars between cattle and sheep operators, with bloodshed occurring in some areas.

1900s

Between 1904 and 1907, many public domain lands were formally withdrawn as Forest Reserves for the Blue Mountains region: Wenaha (northern Umatilla NF) in 1905; Heppner and Blue Mountains (southern Umatilla NF) in 1906. The forest reserves were intended to conserve the area’s water supply for farmers, reduce

conflict between stockmen, and to protect timberlands and summer rangelands from “destruction and wasteful use.” In 1905, just prior to establishment of the Wenaha Forest Reserve, the northern half of the Umatilla National Forest supported somewhere in excess of 275,000 head of grown sheep plus their increase, 40,000 head of cattle, and 15,000 head of horses. All these animals grazed annually on what is now the Pomeroy and Walla Walla Ranger Districts. 1905 was considered to represent a low point for big-game animals (elk and deer) on the Umatilla National Forest. After the Forest was established in 1908, wild game increased steadily: 1938 estimates put the populations at about 10,000 deer and 7,000 elk. In 1906, the open-range wars ended when the U.S. Forest Service began regulating use of summer range by allotting separate areas of the forest reserves to cattle and sheep (and by not allowing the two stock classes to intermingle on the same range). In 1907, Representative Charles Fulton of Oregon introduced an amendment in the U.S. Congress to prohibit further Forest Reserve withdrawals in the Pacific Northwest. Before

this law went into effect, President Theodore Roosevelt created his famous “midnight reserves” by setting aside 16 million acres, including the Blue Mountains, Colville, and Imnaha forest reserves. In 1908, the Heppner, Umatilla, Wenaha, and Whitman national forests were established by Presidential executive order (all of these forests contained lands now included within the Umatilla National Forest boundary). Umatilla National Forest established by proclamation on June 13, 1908.

1910s

As was the case for much of the western United States, the Umatilla National Forest experienced very high levels of forest fire activity in 1910 – more than 97,000 acres burned, a greater acreage than was recorded for any other year in the Forest’s history. In the second half of the 1910s, a large outbreak of mountain pine beetle occurred across the Blue Mountains; the first insect-control project in the country occurred in 1910 when $5,000 was diverted from the nation’s firefighting account to combat beetle damage in northeastern Oregon. In 1915, a Forest Supervisor’s office for the Umatilla National Forest was established at Pendleton in the Post Office building, having been moved there from Heppner. Elk were transplanted to the Wenaha National Forest and the northern Blue Mountains in February 1913 (Pomeroy area), March 1913 (Walla Walla area), winter of 1918 (Blue Mountains near Walla Walla), and January 1930 (south of Dayton, WA). The source of

these transplanted elk was Montana.

1920s

In November 1920, the Wenaha National Forest (containing lands now administered by the Pomeroy and Walla Walla Ranger Districts) was combined with the Umatilla National Forest to the south, and the combined unit was called the Umatilla National Forest.

1930s

In 1935, U.S. Highway 395 was completed as a paved road. This highway is a major north-south transportation corridor for the southern half of the Umatilla National Forest, and for the remainder of the central and southern Blue Mountains. Late in 1937, the Camas Creek timber sale was awarded to the Milton Box Company of Milton, Oregon. This was the largest timber sale ever awarded on the Umatilla National Forest: 221.3 million board feet. Throughout the 1930s, much work was accomplished on the Umatilla National Forest by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a “New Deal” initiative instituted during the Great Depression by the Franklin D. Roosevelt presidential administration. Fire fighting, trail construction, recreation site development, tree planting, building construction, range improvements, precommercial thinning, and a variety of other work was accomplished by the CCC. The Umatilla National Forest had CCC camps at Ukiah, Bingham Springs (on the

Umatilla River), Wilson Prairie (Heppner), near Pomeroy, and at several other locations. The 4-mile road from Tollgate to Target Meadows, where soldiers from Fort Walla Walla went each summer for gunnery practice, was completed by CCC crews. In the late 1930s, the Blue Mountain Ski Club continued developing a winter sports playground called the Lookingglass Creek bowl near Tollgate. Ski lift planning commenced in August of 1938 for what would eventually become the Spout Springs ski area.

1940s

The Harris Pine Mills timber processing plant opened in Pendleton in May of 1940. Much of the timber removed from the Camas Creek timber sale area (located on the North Fork John Day Ranger District) was processed into wood products (fruit shipping boxes, furniture, lumber, etc.) by the Harris Pine Company. Beginning in the early 1940s, national forest tree harvests increased to meet a heightened demand for wood products during World War II, and to provide raw materials for new housing after the war. Annual harvest levels reached 39 million board feet on the Umatilla National Forest in 1944 (cut volume). What is now the Tollgate Work Center opened as a Ranger District office in late summer or fall of 1941, just before District Ranger Albert Baker retired in December of 1941. During this era, Walla Walla was an “in-and-out” district because it had two offices: one at Walla Walla as the winter headquarters, and another at Tollgate as the summer office. From 1944 to 1958, a huge outbreak of western spruce budworm affected the entire Blue Mountains, with almost 900,000 acres of the Umatilla National Forest affected in 1950. From 1945 to 1947, a localized outbreak of Douglas-fir tussock moth occurred on the northern Umatilla National Forest near Troy, Oregon; 14,000 acres of the infested area were sprayed with an insecticide called DDT in June of 1947.

1950s

Spray projects were completed on portions of the Umatilla National Forest in 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1958. During these projects, an insecticide called DDT was applied from aircraft to suppress western spruce budworm populations. Timber harvesting on Blue Mountains national forests began in earnest in the mid 1950s,

when most sales were partial cuts where only the most valuable trees were removed. On the Umatilla National Forest, annual timber harvest levels reached 89 million board feet by 1959 (cut volume). On September 17, 1950, a ceremony was held at Big Saddle, near Table Rock lookout, to dedicate the Kendall Skyline Road. This road was named in honor of William H. Kendall, an early District Ranger (prior to 1920) who was instrumental in the road’s conception and development. Although private funds built the first few miles of this road during World War I, federal funds ultimately constructed most of it, including countless hours by CCC work crews during the mid 1930s. At one point, the Walla Walla CCC camp included 216 young men, many of whom spent time on road projects such as the Kendall Skyline Road.

1960s

By the mid 1960s, small timber sales were made on the north end of the Umatilla National Forest (Abels Ridge and other areas on Pomeroy RD; Swamp Creek and other areas on Walla Walla RD). These early clearcuts now support vigorous, second-growth stands of mixed conifers, and many of them have been thinned several times since the 1970s. In 1968, two research natural areas were designated on the Umatilla National Forest, both of which are located on the Pomeroy Ranger District: Pataha Bunchgrass RNA in Garfield County, and Rainbow Creek RNA in Columbia County. In the late 1960s, a 55-foot-tall dam (about 350 feet long) was developed along Mottet Creek to create Jubilee Lake on the Walla Walla Ranger District. The lake was dedicated on June 1, 1968. The lake area had long been considered for an impoundment; the first US Forest Service site survey occurred in the 1930s. Like Bull Prairie Lake on the Heppner RD, Jubilee Lake development was financed by the Oregon Game Commission using funds generated from fishing license fees. Jubilee Lake covers about 100 acres (second

only in size to Olive Lake on the Umatilla NF), and it is a major recreation attraction.

1970s

Between 1972 and 1974, the northern Blue Mountains experienced the largest outbreak of Douglas-fir tussock moth ever recorded anywhere in North America. The Forest Service eventually convinced the Environmental Protection Agency to temporarily suspend their 1972 ban of DDT so it could be used against tussock moth; more than 426,000 acres were sprayed with DDT in a tri-State area in 1974, with only 32,700 of the sprayed acres located on the Umatilla National Forest. In the mid and late 1970s, many salvage timber sales were completed to remove trees killed or damaged by Douglas-fir tussock moth defoliation. About 137 million board feet of

timber was salvaged from tussock-moth areas on the Pendleton Ranger District alone. In the mid 1970s, a very large mountain pine beetle outbreak occurred in lodgepole pine forests throughout the central and southern portions of the Blue Mountains – more than 375,000 acres of the Umatilla National Forest were affected in 1976.

In 1972, four management treatments were installed at the High Ridge Barometer Watershed – large clearcuts, small clearcuts, selective cutting, and an untreated (control) area. The High Ridge study was initially established in October of 1967 to document weather

conditions for a high-elevation watershed, and to monitor water flow and sediment production changes associated with timber production practices. In the early 1970s, the upper portion of the Tiger Creek (Tiger Canyon) road was developed, with initial work commencing in July of 1971. This is a major recreational road and access point to the Umatilla National Forest for residents of Walla Walla, Washington. The Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness was created by passage of the Endangered American

Wilderness Act of 1978.

1980s

On January 15, 1980, nearly 2,000 skiers flocked to the opening of the Bluewood Ski Area located 23 miles south of Dayton, Washington. In October of 1980, the Woodland Sno-Park site, located about 2 miles south of the Spout Springs ski area and adjacent to Oregon Highway 204, was completed and opened. Like other snow parks, this project was developed cooperatively by a state’s Department of Transportation, Boise Cascade Corporation, and a local snowmobile club. From the late 1970s to the late 1980s, very high levels of timber harvesting occurred on Blue Mountain national forests. On the Umatilla National Forest, annual harvest levels

reached 222 million board feet in 1973, and 227 million board feet in 1989 (cut volume). Beginning in 1980 and continuing until 1992, a large outbreak of western spruce budworm affected the Umatilla National Forest (and the remainder of the Blue Mountains). Several suppression (spray) projects occurred during this outbreak, when either chemical or biological control agents were applied from aircraft. In 1984, two new Wilderness areas were designated on the Umatilla National Forest: North Fork John Day Wilderness (located on the North Fork John Day Ranger District), and the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness (located on the Walla Walla Ranger District). In the early 1980s, the Umatilla National Forest installed the Data General computer system. This “DG system” represented the first agency-wide implementation of standardized technology throughout all levels and offices of the U.S. Forest Service.

1990s

In 1990, the first comprehensive Land and Resource Management Plan was approved for the Umatilla National Forest. It replaced a group of so-called “unit plans,” all of which were prepared and approved in the 1970s, covering smaller portions of the Forest. The 1990 Forest Plan established management direction for a 10-year implementation period (at most 15 years), but it is still in place today. In April 1991, the Blue Mountains Forest Health Report was released. This report described deteriorating forest health conditions on the Umatilla National Forest (and the remainder of the Blue Mountains). Between 1992 and 1994, several broad-scale reports pertaining to the Umatilla National Forest were released. The Caraher Report was issued in July 1992. A draft version of the Everett Report was released in April 1993, with the final report produced in 1994. The Eastside Forests Scientific Society Panel report was published in August 1994. The Eastside Screens were issued in August 1993 in response to a petition and threatened lawsuit from the Natural Resources Defense Council. The Screens established interim direction that all timber sale projects are required to meet. Following a lawsuit filed by Prairie Wood Products, the Eastside Screens were required to meet NEPA requirements by amending the Umatilla Forest Plan. The Screens are still in force today. In March 1994, interim strategies for managing anadromous fish-producing watersheds in

eastern Oregon and Washington, Idaho, and portions of California sued. This interim direction is geared toward restoration of aquatic habitat and riparian areas on lands administered by the Forest Service and BLM; PACFISH is still in force today. On January 21, 1994, the Chief of the Forest Service and the Director of the USDI Bureau of Land Management signed a charter establishing the Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project (ICBEMP). This project resulted in broad- and mid-scale scientific assessments covering more than 144 million acres (76 million of which are federal) in seven western states. Although the environmental impact statement that would have amended the Umatilla Forest Plan was never completed, the ICBEMP effort still produced a wealth of scientific information that continues to influence management of the Umatilla National Forest today. In 1996, a large amount of wildfire activity occurred on the southern half of the Umatilla National Forest, with the Wheeler Point (Heppner RD), Tower, Bull, and Summit (North Fork John Day RD) fires affecting more than 72,000 acres of national forest lands. During the 1990s, timber harvest levels declined dramatically; recent timber harvest levels for the Umatilla National Forest (from the mid 1990s to the present) are the lowest they have been since the mid 1950s.

2000s

Late in the 1990s, a long-term nemesis of the Umatilla National Forest – Douglas-fir tussock moth – once again reached outbreak status, and more than 39,000 acres were sprayed with a natural virus in June and July of 2000 to minimize defoliation damage. In the mid 2000s, several very large forest fires occurred on the Umatilla National Forest, with the School Fire burning about 28,000 acres of National Forest System lands in 2005 (Pomeroy Ranger District), the Columbia Complex Fire affecting about 50,000 acres in 2006 (Pomeroy and Walla Walla Ranger Districts), and the Monument Complex Fire covering about 19,800 acres (Heppner Ranger District). In the late 2000s, moose numbers on the Umatilla National Forest increased to the point where they were no longer considered a transient animal, and it is now assumed that a resident population has gotten established.

Painted Hills and Fossil Lands

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

It comprises three separate locations: The Sheep Rock Unit, The Painted Hills Unit and the Clarno Unit. Each site has short trails to dramatic views of colorful rock formations. The Sheep Rock Unit, home to the Paleontology Center, is between the towns of Dayville and Kimberly on Highway 19 two miles north of Highway 26. The Painted Hills Unit is nine miles northwest of the town of Mitchell, with the entrance six miles north of Highway 26 on Burnt Ranch Road. Find the Clarno Unit on Highway 218 about 20 miles west of the town of Fossil. All three sites will give you a view into the earth’s biography through the plant and animal fossils and rock layers.

Recent History: East of the fossil beds in the town of John Day, the Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site is an imperative stop for a look at the more recent past. Walk through a veritable time capsule of the late 19th and early 20th century in this small building, which first opened in the late 1800s and served as a Chinese apothecary, general store and social hub for what was once the third largest China town in the country. The store was also the home to its proprietors, Ing “Doc” Hay and Lung On, who lived here for more than 50 years.

Other Adventure: John Day is the point of departure for the Old West Scenic Bikeway, a challenging 174-mile loop ride through the remote beauty of John Day Fossil Bed country. Ride the route as a multi-day adventure, or just sample part of it.

The Eat's: Don’t miss 1188 Brewing Company for craft beers like the Box Canyon Pale Ale as well as a hearty menu of sandwiches, salads and wraps. Try the Oxbow Restaurant & Saloon in Prairie City for lunch and nearby Roan Coffee Company for a caffeinated pick-me-up.

Sleep: The Historic Hotel Prairie in Prairie City first opened in 1910 and underwent a complete renovation in 2008. The charming two-story brick hotel puts you in the heart of town. In the town of Mitchell, the Painted Hills Vacation Rentals offer two charming guest cottages, each with a private garden and full kitchen. For a genuine country getaway, check out the Triple H Homestead in the town of Monument. Spend the day hiking, fishing or horseback riding and cozy up in the bunkhouse at night.

The Clarno Unit: is the northernmost unit within this national monument. There are restrooms with non-flush toilets and hand sanitizer, and a picnic area near the parking lot. The most striking feature within this unit are the tall Palisades, looking like ancient battlements on the hillside. The Palisades are remains of lahars (volcanic mud and ash flows) that flowed down the flanks of an ancient volcano, mowing down any plant or animal in the way. There are three very short trails taking you to different viewing angles of these ancient lahars. See if you can spot any fossil plants embedded in the rocks. I didn’t, but my fossil-finding powers are a little on the rusty side. If you do see any fossils, just take photos of them and please leave them alone. It is illegal to take fossils from any of the 3 units of this national monument.

The Painted Hills Unit: Here, one can spend an entire day from dawn to dusk, photographing and hiking these “painted” hills. Different weather and lighting conditions dramatically change the appearance of these stunning striped hills. Sunny days cause the soils to pop with saturated color. On overcast days, the undulating folds of these hills look like shadowy, rich, maroon-and-olive-striped velvet. The red/maroon – yellow/olive green layers are examples of ancient climate change. During wetter periods, the iron minerals oxidized and turned the soil red, while drier periods are represented by non-oxidized yellow-ish colors. These wet and dry periods also accommodated different ecosystems. Near the Red Hill Trail, you’ll see a small white hill, indicating the remains of a 39-million-year-old superheated ash and gas flow covering the land and marking the boundary between the older Clarno Formation and the younger John Day Formation. The road through the Painted Hills Unit is easily-navigable gravel. There are no restrooms except at the entrance, where there is also a small information center with trail, camping & available services, and regional maps of the national monument. There are 5 short trails within this unit, ranging from .25 – 1.6 miles round-trip. The longest trail is the Carroll Rim Trail, which I highly recommend for a stunning panoramic view of this unit. As you walk along the trails in between these painted hills, take a close look at your surroundings. Notice the texture and patterning of the colorful soils. Listen to the birdsong. During my visit, I heard the honking of geese as they flew low between the hills. Of course, you’ll want to get plenty of wide-angle shots of the landscape, but use your telephoto lens or telephoto setting, as well. Zoom in to capture the light and shadow rippling over the hills. Isolate one or two of the sparse trees growing atop those hills. Look closely at the textures of the crumbly soils. Capture some "leading line" images of the trail you are on. Leading lines move the viewer's eye from one part of the photo to the other, allowing the eye to linger on the image and take in more detail. Remember, panoramic shots present the Big Picture, but telephoto images flesh out the story of Painted Hills creation.

The Sheep Rock Unit: This is the largest unit of the three, with many available photo ops of the beautiful and colorful geology and scenery. Stop at any of the pullouts to marvel at the columnar basalts of Picture Gorge. Sheep Rock Unit is home to the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, housing display cases filled with fossil specimens of plants and mammals, and walls decorated with huge, colorful murals depicting ancient landscapes millions of years ago. There’s also a working lab with a large picture window through which you can watch a technician painstakingly clear away rock matrix around a fossil nut, leaf, or bone. After your visit to the paleontology center, why not stretch your legs on nearby trails such as the Thomas Condon Overlook, the Island in Time trail at Blue Basin, or drive five miles further north to the Foree area for a couple more short hikes with gorgeous vistas. Don’t let bad weather stop you from marveling at the colorful rock formations. Rain actually saturates those shades of pinks, greens and yellows. If you feel like learning a little history about the settlers who lived there, check out the James Cant Ranch House, renovated to accommodate park headquarters and a museum. One more stop before you end your day should be the Mascall Overlook, just off Hwy 26 heading east toward the town of John Day. From this vantage point, you’ll see the Upper John Day Valley, the Strawberry Mountain Range, Picture Gorge, and the Mascall and Rattlesnake formations.

On a trip like this there is never enough time to see and explore the three units in John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. After a visit there, you’ll return home with beautiful photos and a better understanding of the life and ecosystems that existed millions of years ago in what is now eastern Oregon however, you'll be returning for more adventure before you know it!

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

It comprises three separate locations: The Sheep Rock Unit, The Painted Hills Unit and the Clarno Unit. Each site has short trails to dramatic views of colorful rock formations. The Sheep Rock Unit, home to the Paleontology Center, is between the towns of Dayville and Kimberly on Highway 19 two miles north of Highway 26. The Painted Hills Unit is nine miles northwest of the town of Mitchell, with the entrance six miles north of Highway 26 on Burnt Ranch Road. Find the Clarno Unit on Highway 218 about 20 miles west of the town of Fossil. All three sites will give you a view into the earth’s biography through the plant and animal fossils and rock layers.

Recent History: East of the fossil beds in the town of John Day, the Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site is an imperative stop for a look at the more recent past. Walk through a veritable time capsule of the late 19th and early 20th century in this small building, which first opened in the late 1800s and served as a Chinese apothecary, general store and social hub for what was once the third largest China town in the country. The store was also the home to its proprietors, Ing “Doc” Hay and Lung On, who lived here for more than 50 years.

Other Adventure: John Day is the point of departure for the Old West Scenic Bikeway, a challenging 174-mile loop ride through the remote beauty of John Day Fossil Bed country. Ride the route as a multi-day adventure, or just sample part of it.

The Eat's: Don’t miss 1188 Brewing Company for craft beers like the Box Canyon Pale Ale as well as a hearty menu of sandwiches, salads and wraps. Try the Oxbow Restaurant & Saloon in Prairie City for lunch and nearby Roan Coffee Company for a caffeinated pick-me-up.

Sleep: The Historic Hotel Prairie in Prairie City first opened in 1910 and underwent a complete renovation in 2008. The charming two-story brick hotel puts you in the heart of town. In the town of Mitchell, the Painted Hills Vacation Rentals offer two charming guest cottages, each with a private garden and full kitchen. For a genuine country getaway, check out the Triple H Homestead in the town of Monument. Spend the day hiking, fishing or horseback riding and cozy up in the bunkhouse at night.

The Clarno Unit: is the northernmost unit within this national monument. There are restrooms with non-flush toilets and hand sanitizer, and a picnic area near the parking lot. The most striking feature within this unit are the tall Palisades, looking like ancient battlements on the hillside. The Palisades are remains of lahars (volcanic mud and ash flows) that flowed down the flanks of an ancient volcano, mowing down any plant or animal in the way. There are three very short trails taking you to different viewing angles of these ancient lahars. See if you can spot any fossil plants embedded in the rocks. I didn’t, but my fossil-finding powers are a little on the rusty side. If you do see any fossils, just take photos of them and please leave them alone. It is illegal to take fossils from any of the 3 units of this national monument.